Conceptual

Fictions

(Archae Editions, Ridgewood-Soho,

New York, 2012)

About the Project:

From Conceptual Fictions:

The radical idea posited by Conceptual Art in the 1970s was that prose statements alone could suggest experiences in the tradition of visual art. It grew out of esthetic minimalism’s hypothesis that more could be experienced with less, much less.

Both conceptual art and esthetic minimalism depend upon contextual framing that was initially realized by bestowing radical new work with the honorific epithet of Art. This could be done by giving a resonant title to slender visible content or by placing it in a credible art context. For an historic precedent, consider how Marcel Duchamp’s urinal, which, purchased in a neighborhood supply store, gained esthetic value from inclusion beside accepted paintings and sculptures in a prominent art exhibition.

Though most conceptual artists use words, sometimes concretely (Robert Barry), other times obscurely (Lawrence Weiner), their wordworks have had little influence upon people who began as writers, except perhaps myself, who fortunately moved in 1974 into that esthetic hothouse known as Artists’ SoHo.

In a visual art context Holly Crawford printed a conceptual narrative consisting only of punctuation marks extracted from a Clement Greenberg text, with all words between the marks removed. (One assumption here is that someone else’s punctuation marks would be visibly different. Or, better, that a writer could compose a narrative entirely of punctuation marks, allowing the reader to imagine what words might fall between.) In a more strictly literary context, David Markson’s miscellaneous book of statements, Reader’s Block (1996), benefited conceptually by being published/billed as “a novel.” Though as no further claim is made for it in that respect, such deviance lacked the critical weight to be noticed (perhaps except by me).

If we can agree that a Conceptual Fiction, in the tradition of Conceptual Art, would suggest with words alone a story that need not be written, or more story than is written, then I’ve been producing such literature since around that time, initially with Openings & Closings (1975), a book of single sentences meant to be, alternately, either the openings or the closings of otherwise non-existent fictions.

In the mid-1970s, I also developed the idea of Constructivist Fiction, which consists of symmetrical line-drawing whose squares changed incrementally over a sequence of pages to suggest a narrative before concluding. The narrative experience comes from the reader’s turning the page.

In this context, I published limited editions of Tabula Rasa: A Novel and Inexistences: Stories (both 1978), the former eight inches square, the latter four inches square. Each has a printed cover and spine, a title page, and then a single page with contextual information. As all the remaining pages in both books were pristine white, this encasing framing suggests conceptually that the blank pages must contain a narrative.

By the late 1970s I extended the concept of Conceptual Prose to Epiphanies, whose sentences were meant to be the coalescing moments—Epiphanies in the James Joycean sense—of otherwise nonexistent stories, suggesting through only a short text some additional fiction that might have followed and might have come before.

All these texts of mine depend upon strategic framing established with such indisputably literary titles as Fiction, Stories, Novels, Epiphanies. (Simply, a sentence published under one or another of those rubrics thus differs in value and weight from the same sentence appearing without such a frame.)

Four decades ago, I called this work Inferential Art because so much of the meaning had to be inferred from resonant framing. The pioneering epitome in my mind was John Cage’s so-called silent piece, 4’33” (1952), where the audience was invited to infer from a situation where music was expected, with a known pianist statuesque before a keyboard, that the “music” consisted of the sounds incidentally heard with the announced time-frame. The radical implications held that “music” consisted of all the miscellaneous sounds heard within that space and within that time frame and, then, that significant meaning could be embedded in the initial perception of nothing. (My own In Memory of John Cage (2009) is a thick piece of glass, 13” square, mounted frameless on a pedestal, the inferred theme being that the Art consists of whatever can be seen through this glass.)

What I called Sketchy Stories, collected in Furtherest Fictions (2007), broached the conceptual idea of suggesting a narrative with only a few discrete words, nonsyntactially connected, followed by a period, the closing punctuation mark (which the British call “a full stop”) defining the fragments as fictions. The same principle of closure informs my Two-Element Stories (2003) and 3-Element Stories (1998), both of which contain words that are not obviously connected syntactically.

***

You can see sample pages from Conceptual Fictions over HERE. Some examples of Conceptual Fiction's "words [that suggest] a story that need not be written, or more story than is written" are the words:

This must be the middle of the novel.

or

The action, previously set in the past, now shifts into the present.

Individual entries on Richard Kostelanetz’s work appear in various editions of Readers Guide to Twentieth-Century Writers, Merriam-Webster Encyclopedia of Literature, Contemporary Poets, Contemporary Novelists, Postmodern Fiction, Webster's Dictionary of American Writers, Baker's Biographical Dictionary of Musicians, Directory of American Scholars, Who's Who in America, NNDB.com, Wikipedia.com, and Britannica.com, among other distinguished directories.

The painting of Richard Kostelanetz (right) is by Leonid Drozer.

Mr. Kostelanetz shares the following:

ENGLISH-CENTERED WRITING:

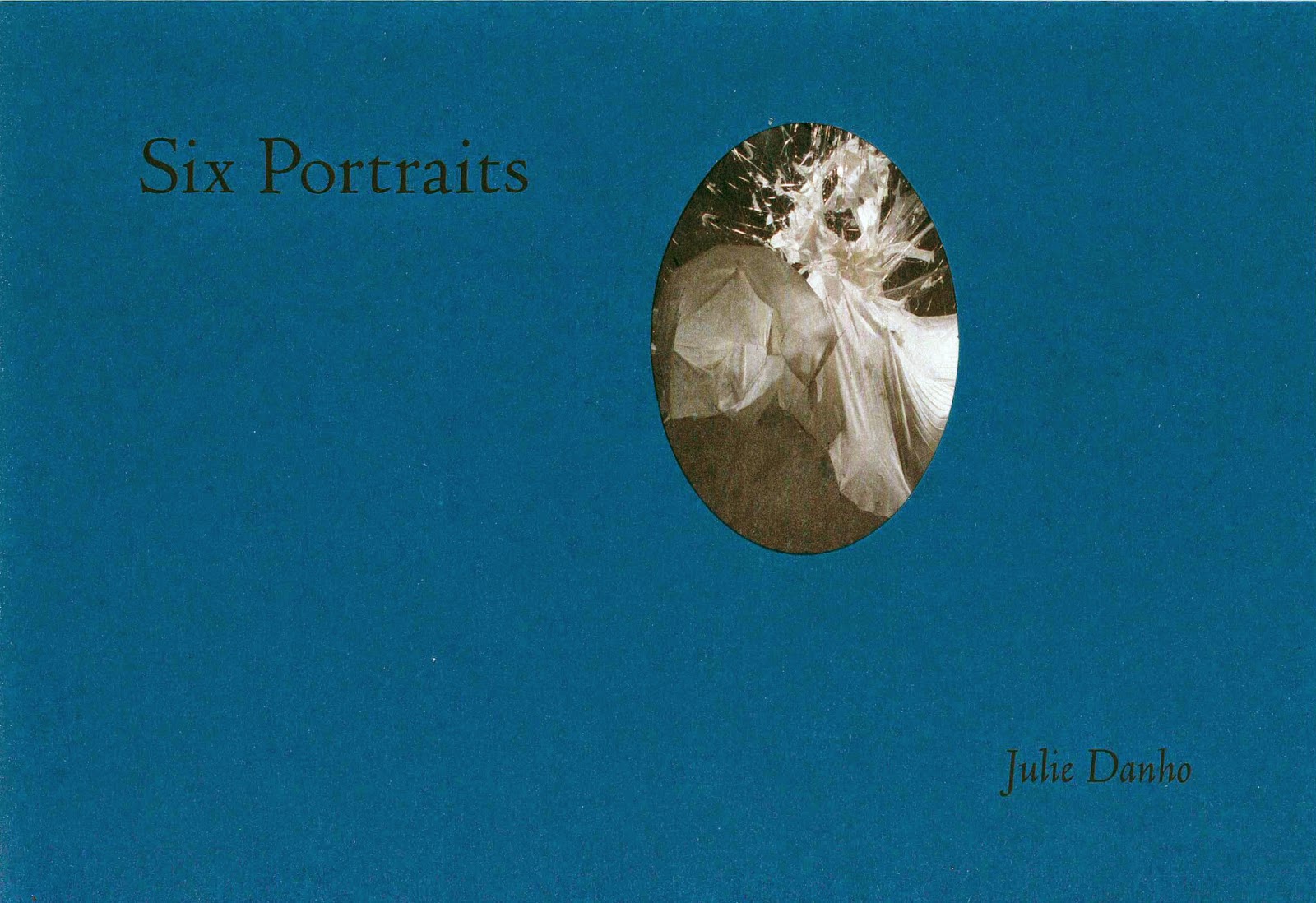

In a recent series of

books at the nexus of literature and book-art, mostly available from Archae

Editions on CreateSpace (Amazon) unless otherwise noted, I explore certain

qualities in my native tongue.

Ambiguities (2014) are sentences that have at least two

decidedly different meanings.

Cunning Commas (forthcoming) has two (and sometimes three)

sentences of the same words made different through the addition of commas and

other punctuation marks.

Cunts after J Updike (2013) collects with highly imaginative typography

over one hundred synonyms for the female sexual organ.

Curious/English (2013) likewise present continuously on opposing

pages English words with those different contrasting qualities.

Double Doubles (2013) contains very short sentences in which at

least one pair of words has different meanings.

English English (forthcoming) explores the same variation through

duplication of a single loaded word in longer sentences.

English, Incredible

English (2013) collects in fourteen

thick volumes over 7,000 English words, stylishly printed alphabetically one to

a page.

Filling Holes (forthcoming) depend upon presenting on one page two

collections of letters that are separated by a space that, on the next page, is

filled with a letter that connects its parts to make a single English word.

Forth&Back& (2013) consist of pairs of words, printed on both

sides of a single page, each pair in a typeface unique to itself, that can be

read in either direction.

Fucks (2014) explores various meanings for notorious word.

Ghosts (Unicorn, 2006) depend upon discovering within the

letters of a single word another shorter words that critically relates to its

host.

Grammatolatries (2014) has absurd sentences set in an archaic

typeface reminiscent of newspaper headlines.

Homographies (2013) are short sentences containing certain

English words used in two different ways.

Homophones (2013) makes micro fictions wholly of English words

that sound alike.

Incongruities (2014) has English sentences with internal

contradictions.

Loveliest/Ugliest

English (2013) present continuously

on opposing pages with consistently different typefaces English words with

those contrasting qualities.

Mirrors (forthcoming) consists of English words that

duplicate around a central axis (e.g., racecar).

One-Letter Changes (2013) makes narratives from two English words whose

successor differs from its predecessor by only one letter.

Ouroboros (forthcoming) are English words which, when typeset

in a circle, suggest other words.

OuroboroStories (forthcoming) makes of such circles continuous

narratives.

Recircuits (NY Quarterly, 2009) are handwritten sequences of

English words whose semantic changes with the addition of a single letter.

Roundelays (forthcoming) composes rectangles from the same

letters that, in different sequences, produce different words.

Shifting Sounds (2014) has sentences in which the same spellings are

pronounced differently.

Squares (2013) finds, from reordering consecutively the

letters of an English word in successive lines, the presence of other words.

Three Poems (NY Quarterly, 2011) has three sections. “Bassaskenglish”

contains English words whose letters are reordered to suggest other meanings. “Monopoems”

has individual words weighty enough to attain poetic resonance simply by

standing by themselves. “Coming(s) Together” takes apart whole English

words to reveal other English words with different meanings.

Three- &

Two-Letter Texts (2013) collects

very short English words.

Tri/ni/ties (2013) has over 130 words divided into three parts

that are set in triangles where the top of the words face a center, bound back

to back with a few Quad/ri/ni/ties.

Triangles (2013), bound back to back with Squares,

explores a more severe constraint both vertically and horizontally.

Perhaps certain other

earlier books of mine, as well as certain collections in progress, belong on

this list. I’m not aware of anyone else producing other books like any of them.

So unique to English are

these texts that none of them can be translated into another. Some I would

classify as Poetry because they realize a concentration of effect within a

highly constraining form; others are Essays for defining qualities unique to

English. All exemplify the principle, important to me, of radical formalism.

All sit on the nexus of Literature and Book Art.

--Richard Kostelanetz